He wanted to keep working on his novel and tried to dictate edits to my Mom. He talked on the phone with his friend John about a math problem they had been working on for several years involving ants—unless you are a mathematician, don’t ask. He kicked around a soccer ball with my brother Ben, really short distances.

He ran with me. I’d run just in front of him and call out to him “pot-hole coming on our right” “people up ahead, we are going to move out to the left around them” “uneven road here, Dad”. I made him a series of iron-on tshirts that said BLIND GUY, BLIND GUY RUNNING, BLIND GUY DRAWING. Partly this was genuinely to let people know he was blind. People jostled him and bumped into him shockingly, even once he got the white cane. I mean really, watch where you’re going folks.

But he quickly went blind and most of these activities dropped away. For a long time he would have visual fantasies or visions. The brain keeps firing visual imagery even when the eyes aren’t providing any information. He would see misty Japanese gardens from a Sumi painting one day, canyons opening below him the next. He often startled when you walked with him because he was seeingsome phantasmal object you were about to walk him right into. Why would you do that?!

The blindness was one of the scariest things to me. I can’t really think of anything scarier, except maybe endless pain. Which is actually a good thing about brain tumors. Weird thing about the brain, but the brain doesn’t feel pain. No nerve endings in the brain. And unlike many with brain tumors, Dad never really had headaches. He also sailed through radiation and chemo with only one episode of barfing and one small set of seizures. He was just kind of amazing through it all.

Dad’s response to the horror and unfairness of what was happening to him was to just let it all go. He handled it with utter grace and kindness. He was grateful for everything we did for him. He never grew irritable or angry or difficult. One of the nurses told us early on that radiation tends to make people more of what they are. So if someone was aggressive and angry, they might become more so. Dad became sweeter and sweeter.

Can you see anything from where you stand?

My Dad was amazing about the whole process, so open and generous with it. But he wasn’t really that interested in talking a whole lot about death or what was coming. He was pretty happy staying in the present moment and finding peace and pleasure everywhere he could. Sometimes I would press him about what he wanted, what he understood about his situation, what it felt like. As a poet and a pretty deep guy, we were hoping Dad would “write” or dictate something about his experience; we were hoping for deep thoughts about life and death from someone so close to the edge of existence.

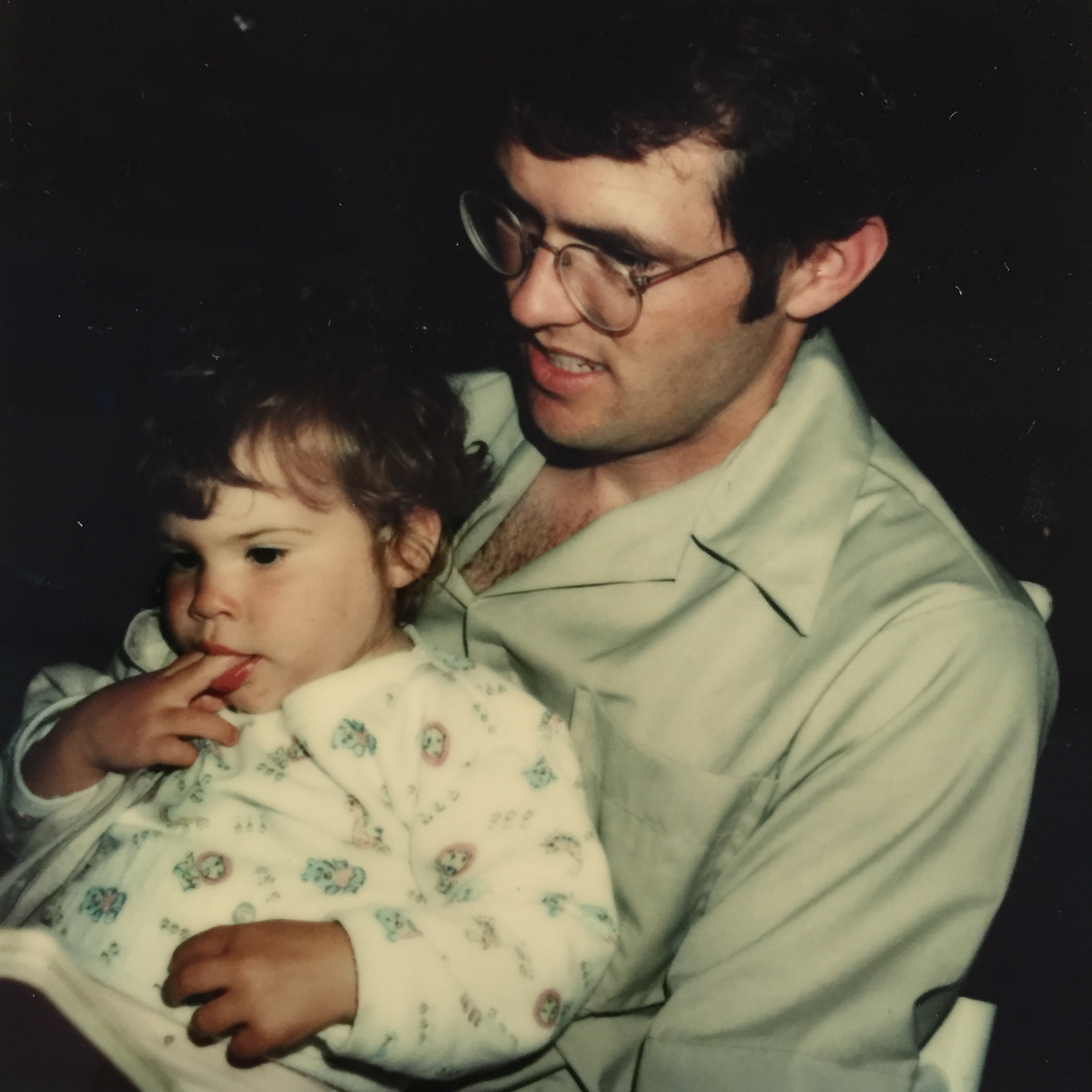

But mostly the time slipped by in regular life chores and distractions. I spent most of the time I was there with Dad taking care of my son Hazard. I cleaned the house vigorously and cooked and helped Mom figure out the medical stuff. We had to make lists and schedules for medications, navigate appointments and treatment, handicap parking passes, bus schedules. All this became normal, unremarkable. I had moments of frustration when I felt like what I should be doing was sitting with Dad and holding his hand and reminiscing, or reading Patrick O’Brian’s Master & Commander books aloud to him. But when it worked best it was the small things like singing along to music in the car with him, making sure he could listen while I read bedtime books to Hazard, making him comfortable and refilling his coffee.

We didn’t have many of the searching talks I thought we might. Dad didn’t talk directly about his situation much and preferred to be out of the room when we had the hard talks with the doctors where things came down to numbers, months. But Mom did get this dictation out of him after a day picking out a Christmas tree with our friend Kelly; so very, very Dad.

As told to Mom by Dad and put into this sort of poem format by me:

So when people ask, “how are you”, you could just hand them the lab report

or say, Well I have cancer! But if you don’t want to come at people that way,

You could say, I have cancer, but I think I would never have had this day

the way it was without it and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

I wouldn’t mind the cancer going away, but if it’s not and it’s not likely to,

Let’s have some more days like this.

Cancer picks you up by the back of your shirt and says,

No, it can’t go on this way forever and you know that, don’t you.

Everything is a gift. This here cancer thing, I can’t call it a gift.

But this day, that was a gift. That was good. Following you all around,

Hearing everything I heard while we picked the tree.

Life in the slow lane

As the months went by the cancer was held at bay. The treatments were working! But Dad continued to deteriorate physically and mentally. We learned that the radiation treatment, which had stopped the growth of the tumors, was continuing to do damage to Dad’s brain. Many people who receive full-brain radiation for brain tumors don’t live long enough to discover this downside. Lucky Dad.

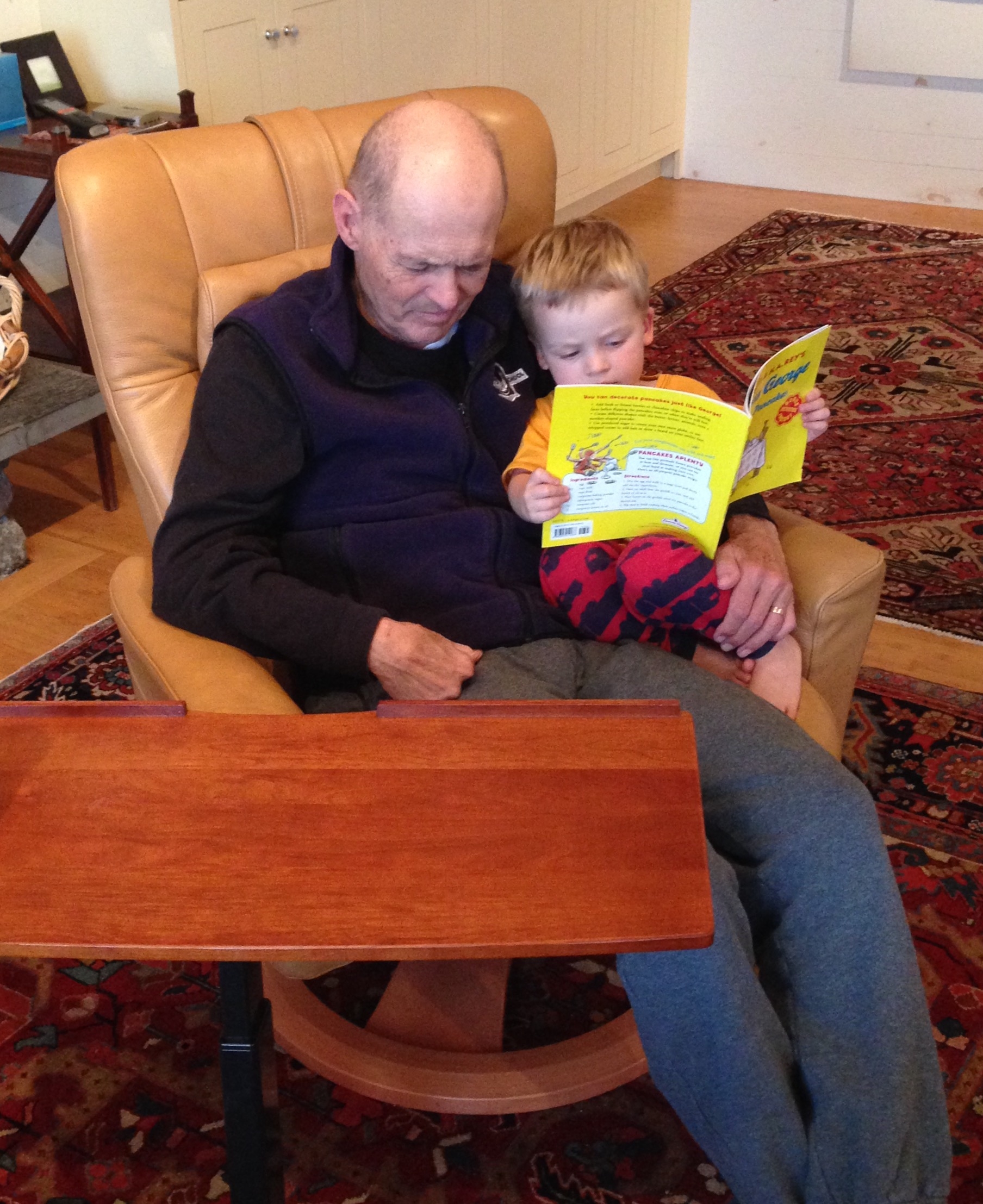

I visited in February during this phase and I saw what Mom was dealing with. The change in Dad and what her day-to-day life had become shocked me. This phase was so hard on Mom, but I genuinely think my Dad was happy. He had told Mom a few weeks before, “You know, a king could not be happier than I am right now. I’ve got you, I’ve got the kids, and I’ve got just the right number of grandchildren. The kids found great partners and they’re doing such a wonderful job bringing those kids up.” He was at peace, enjoying talks with friends, his family and “the baby symphony” as he called kid chaos.

Being a caregiver to a dying person is a bit like having a newborn—very difficult but doesn’t last forever. There was extreme sleep deprivation, physical tolls on Mom’s body, mental fatigue and boredom; the suspended sense of being out of control of your life. Throughout the two years of Dad’s illness and death, I was so impressed by my Mom’s pluck, stamina, good cheer and strength. She would’ve made a great nurse in either of the World Wars (favorite reading subjects of hers). She is not a complainer, not an agonizer. She always told me how her own Waspy mother raised her not to think she was so special or unique, but to be a good hard-working person. This humility and sensibility stood her well when coping with cancer.

The other thing that happens in the long haul of cancer is compassion fatigue in your friends. People really rally at the beginning and at the end; when someone is diagnosed and at death—bringing meals, offering help, stopping by. But cancer can go on and on. You are mostly on your own, possibly for months or years. Many friends stayed with us the whole way through. Some people didn’t visit because they didn’t want to intrude or be a bother or because they just didn’t know what to say; some couldn’t visit, it was just too painful. But Dad loved the visits. Every dying person is unique and there is truly no roadmap, so, if you’re wondering how to handle it, the best bet is to just ask. Ask if visits are wanted or if you can stop by with a meal. You really don’t have to say anything about the whole damned cancer deal, just show up and hang out. Tell stories about what’s going on in your life, a movie you’ve seen, an art show. Since Dad was blind, friends would come and read to him. Our friend Ken would read to him from the Economist and then they’d talk politics and rant, same as always. My brother Ben’s good friend from childhood Ben Campbell would come over and watch soccer games and provide the play-by-play description so Dad could follow along. This was also super helpful to Mom, who could then take a shower or a nap or a walk.

This was the hardest phase for me, aside from the initial diagnosis. I found myself getting mad at my Dad. It was a terrible feeling. There was a point where I felt that this was not really my Dad anymore, but a vampire who had taken over my Dad’s body and was feeding on him and holding us all hostage. Like a benevolent shell of him, with the same voice and way of talking but increasingly just a shadow of his wit and intellect and poetry. And suddenly after a full, rich life of being a regular (if unique and eccentric) person, here was my Dad…The Saint! It wasn’t right, it was too simplistic for the complex, flawed and wonderful human he was. I was mad about what my Mom was going through, about how hard things were for her. I was mad that everything felt on hold, that it was so hard to plan for the future with this huge unknown hanging over us. Mostly I was mad that I was losing my Dad bit by bit. And I felt worse for even thinking these things!

And no one knew how long this phase would last. A few days after Hazard and I had gone back home Mom wrote to Dr. Lynne Taylor, an excellent palliative care specialist we’d recently seen at Virginia Mason in Seattle, asking gingerly what she could expect in the next few months and whether Hospice was a good idea.

Dr. Taylor wrote back kindly and immediately. She couldn’t really tell us much except that Hospice was a good option. She wrote, “All it takes is the possibility that he might die within the next 6 months if the disease takes a typical course, but it is not obligated and I have had patients enjoy the benefits of hospice for up to two years.”

We liked that idea of “enjoying the benefits of Hospice”. Hospice is such a fantastic idea and resource. I wish more people could think of it not as the death knell and more as a way of easing the transition from life to death. But you do have to forego treatment. You have to leave treatment behind, and the idea that you might recover and live. For many this is a step that comes only in the weeks or days before death.

Looking back, the crazy thing is that Mom wrote this email after having been told by the doctors at the UW that Dad could possibly live for months or maybe years. This was daunting, given his decline and his total dependence. It turned out to be much quicker, in only three months he was gone. That is the thing with cancer; no one really knows how it will go or what that will look like. Every cancer patient and his family are reinventing the wheel.