I started writing this piece a year after my Dad died. I’m not sure it will ever be done. There is a draft that is 55 pages and one that is 15 pages. This is a condensed version.

An excerpt of this piece appeared in Actually People Quarterly in 2016.

drawing by Dave Leedy

Lives are attracted here by life

through a door left open on a light.

Both entering and leaving it

are sudden gifts,

both leaving and being left here.

--from Elegy, by Dave Leedy

Why not us?

Cancer stories are like families, all alike and all different. When you’re in that story, it is the craziest most confusing and terrifying and fascinating thing. People are going through it all the time, every day, right now. Husbands, wives, kids, parents, young people who are on their own, old people who have lived full lives, people who are not done yet.

My Dad, David Merrill Leedy, died on May 16th, 2015 from primary brain tumors; a fact that surprises me to this day. It was almost exactly two years from his diagnosis to death. In the beginning there was the inevitable outrage. Dad was so young, so fit and healthy, such a kind good person. He didn’t deserve this. Why US?! But pretty quickly I shifted to “Well, why not us?”.

Cancer, and more truly Death, happens all around us all the time whether we are ready or deserving or not. How you eat and how you live don’t change the end result. We all know this and yet many of us are superstitious and irrationally believe the rules may not apply to us, to our families.

Paul Kalinithi, a neurosurgeon and neuroscientist who died of lung cancer at 36, wrote “Before my cancer was diagnosed, I knew that someday I would die, but I didn’t know when. After the diagnosis, I knew that someday I would die, but I didn’t know when. But now I knew it acutely.”

I adjusted my basically optimistic stance regarding cancer from “this will never happen to me,” to “I will probably get cancer at some point but I will survive!”

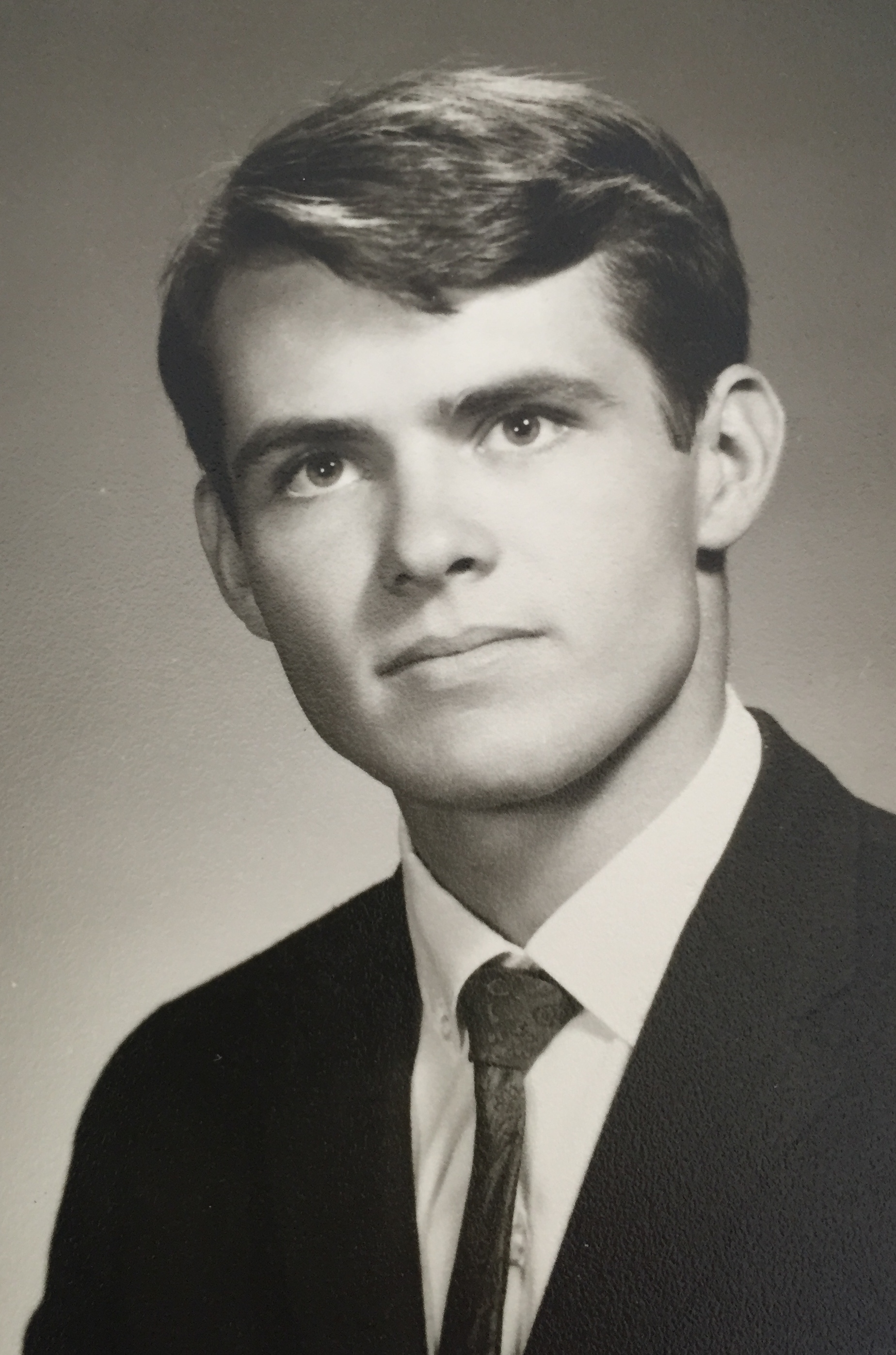

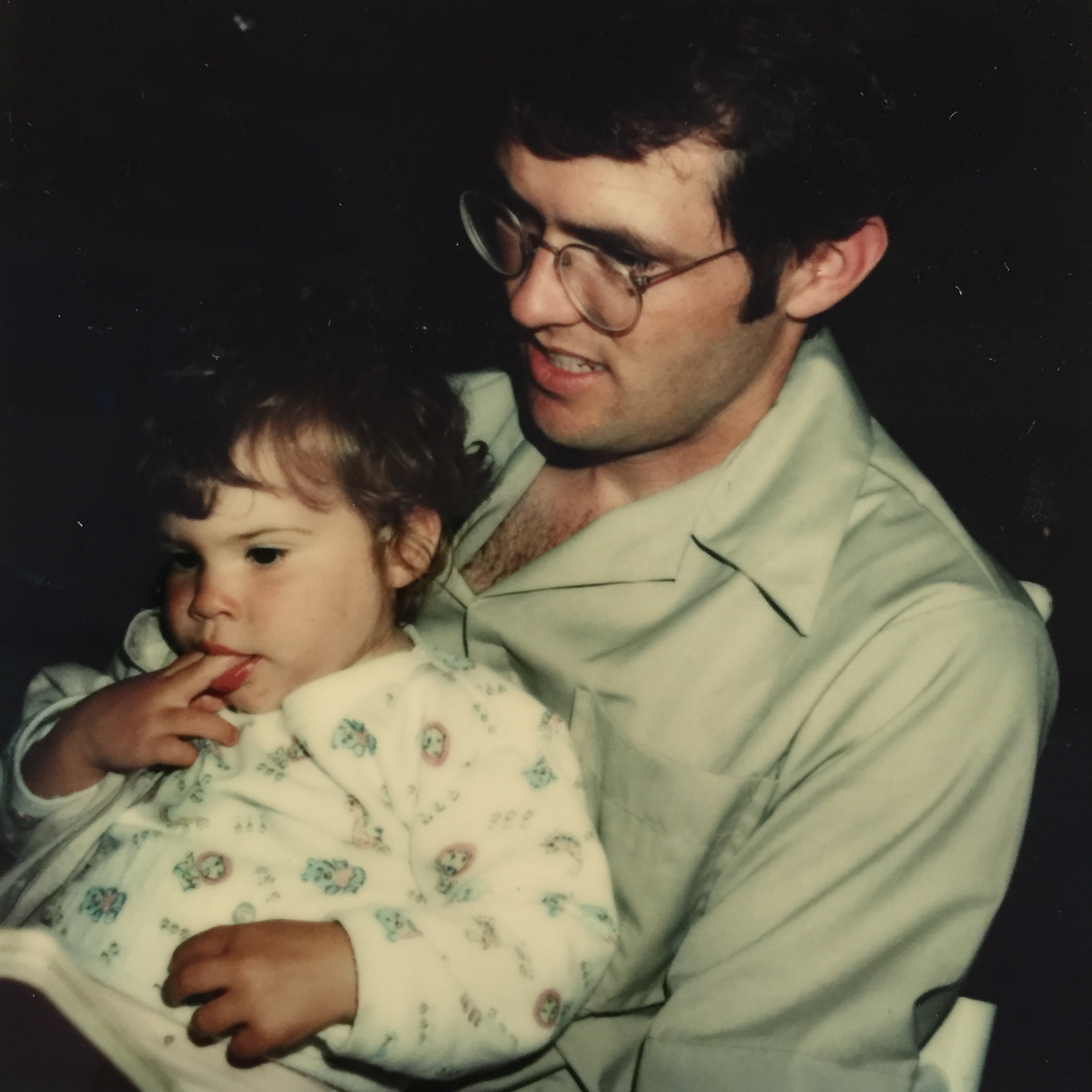

My Dad, David Merrill Leedy

4/10/1947 - 5/16/2015

The hardest part about writing this may be that my Dad edited just about everything I ever wrote. He edited every high school paper and many in college, with me sitting impatiently and eye-rollingly at his side going through sentence by sentence and close reading until we got it just right. I wish I could go over this with him.

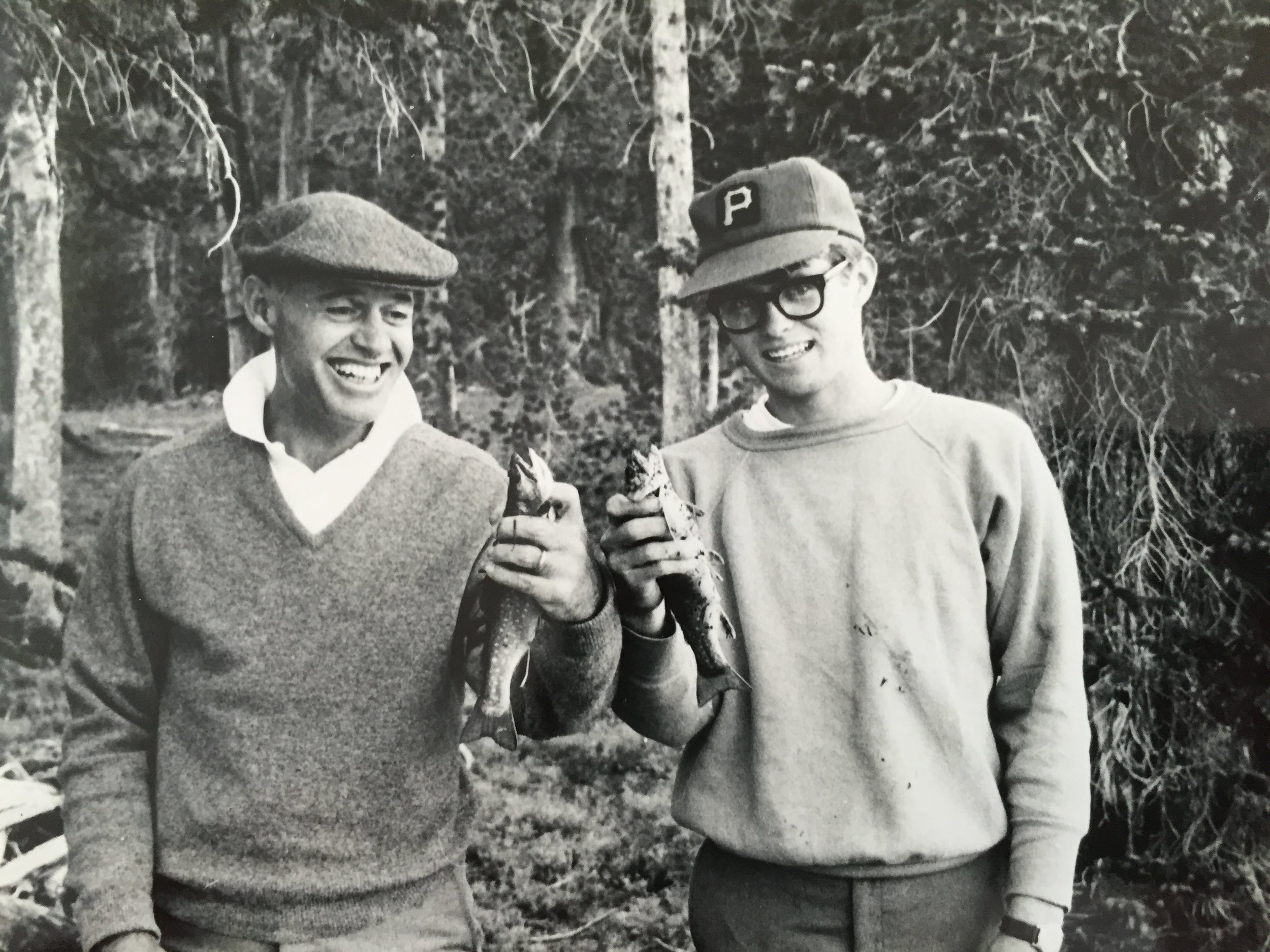

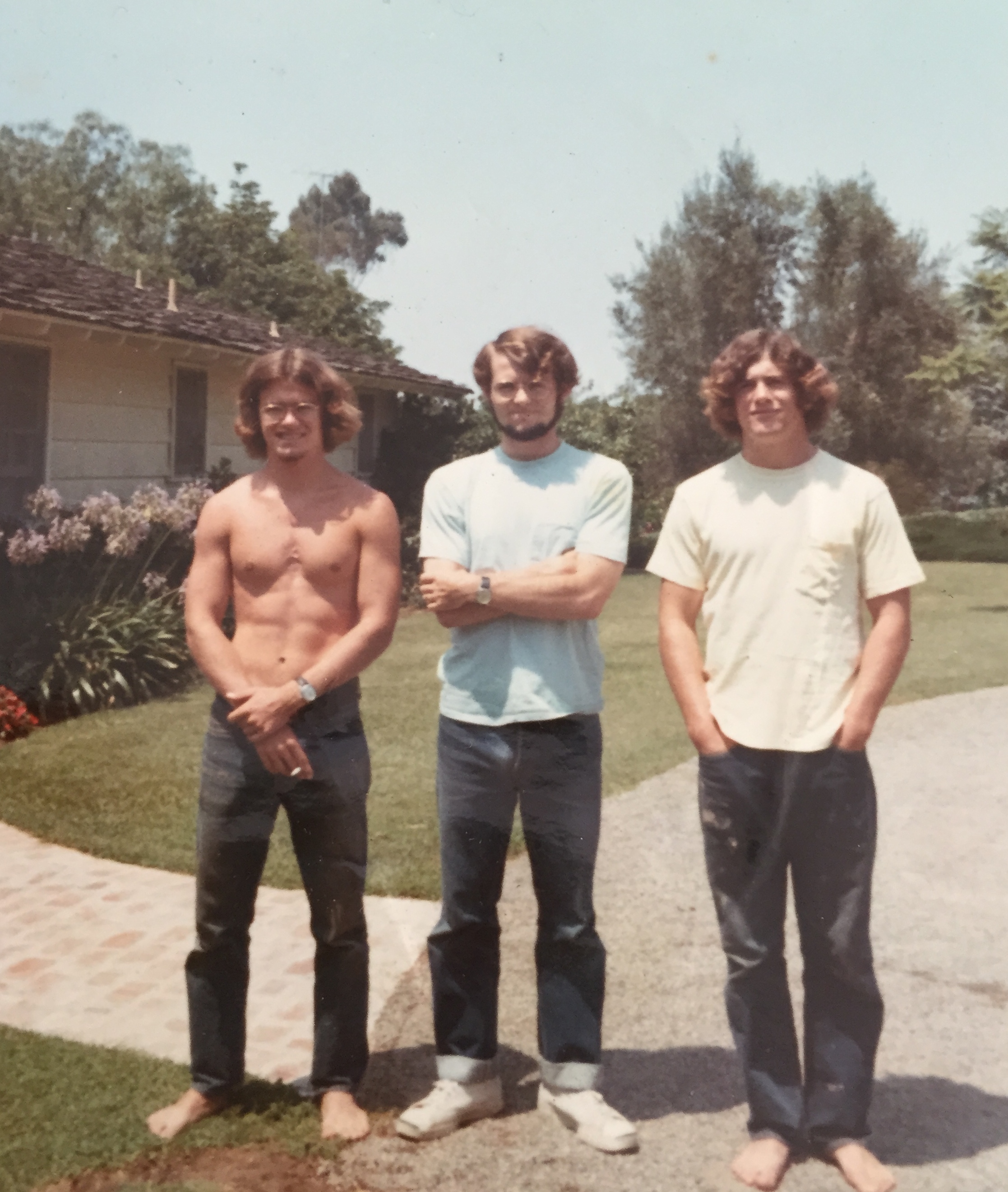

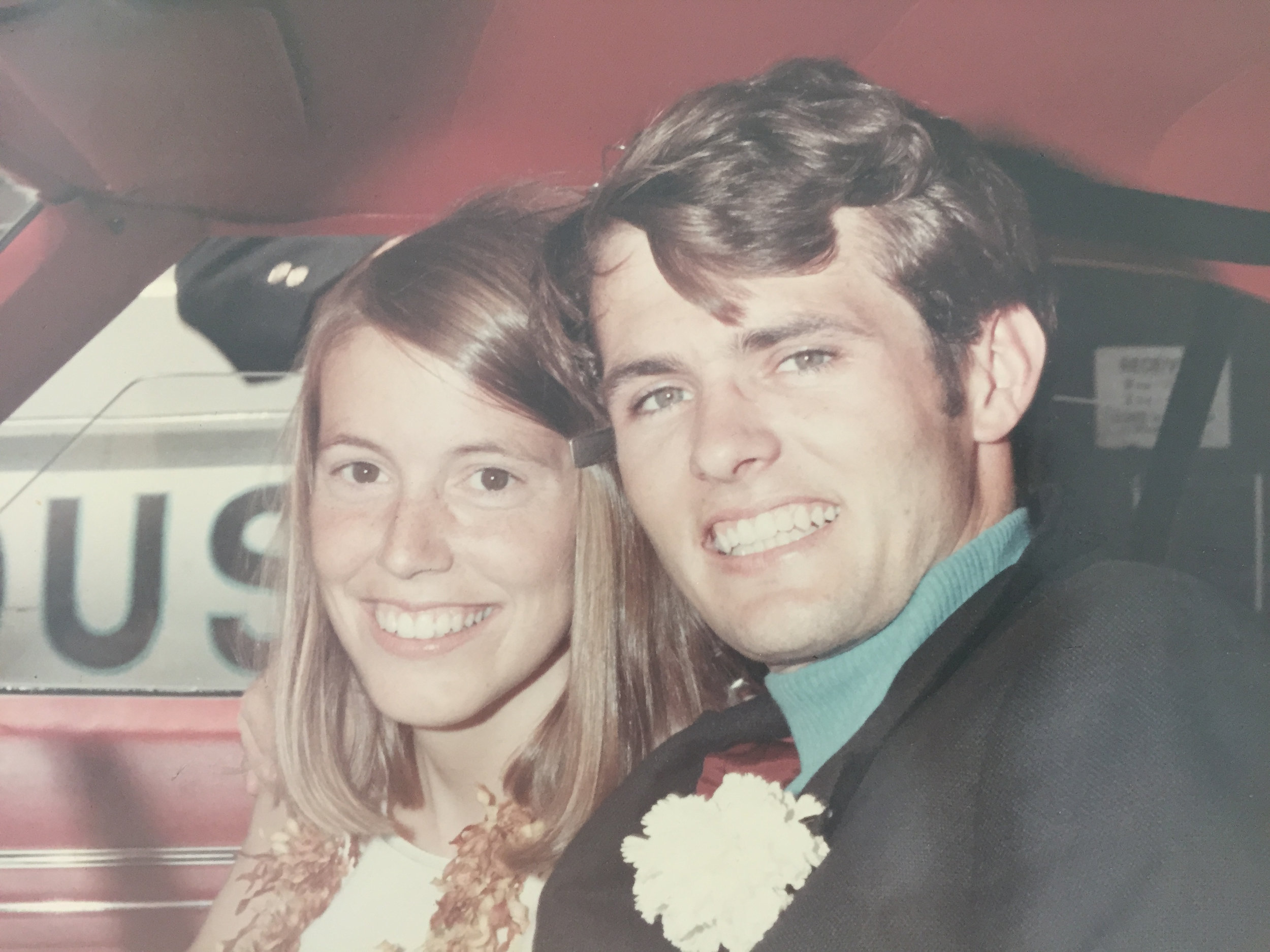

My Dad was a soccer player, a teacher, a writer, an amateur mathematician. He was an altar boy who gave up god and sat zazen until he discovered soccer, “The Church of Soccer” as he called it. He was a star runner in high school and at college. He was also a star football player, baseball player and student. He graduated with honors from Stanford, married my Mom, Nancy, the day after graduation and went on to grad school at Yale with thoughts to be a lawyer or a professor. Then he started quitting things and the first thing he quit was being a star. He tried grad school in philosophy, quit that. He happened into teaching. He took up drawing. He had kids. He worked at a daycare. Then he started a series of schools that got smaller and more eccentric over the years until he had The Green Onions Research Institute, named after the Booker T. & The MGs song and numbering no more than the students he could seatbelt in his van. I came up with his first tshirt logo, an anarchy symbol made of green onions.

I always thought of him as a man who should’ve been a monk working away alone in a medieval cell on the great questions of existence. But he loved the world, loved dogs and movies and politics and family.

A Sampler List of Dad’s Favorite Movies:

Joe Vs. The Volcano

Galaxy Quest

Meet Joe Black

Bandits

Groundhog Day

The Best of Times

Bowfinger

Love Actually

Searching For Bobby Fisher

Duets

It’s the strangest thing

In early June 2013 my parents had just visited for our son Hazard’s first birthday, then continued on to a family reunion. In the airport on their way home Dad told Mom “It’s the strangest thing, I can see right through people.”

When they got home he went to see an eye doctor, an old friend of mine since the 6th grade. He told Dad that this was not an eye thing, this was a brain thing. Then a strange and confusing scramble started. We quickly learned that it was cancer, brain tumors affecting his optic nerve that would soon make him blind, but what kind of cancer remained elusive. Because, of course, where a cancer manifests is not always where it began. And how you treat a cancer depends very much on what kind it is. Primary brain tumors are rare. Usually cancer starts somewhere else—melanoma, prostate, colon, breast—then metastasizes and spreads around the body via lymph nodes, spinal column, blood. Brain tumors are more usually a late stage development. For a month doctors tested and searched and scanned and spinal tapped. A month can be so long.

My Dad did this drawing of Hazard when he was about a month old. He was holding Hazard while he drew

Finally it was determined that Dad had primary brain tumors, and a very rare kind, Glioblastoma cerebreii. After the diagnosis Dad, a life-long hypochondriac who had a long history of imagined cancer, heart attacks and every other malady, told Mom “I always knew it would be fatal, I just didn’t know it would be interesting.” But of course it was. Dad always was unique and special, so we weren’t really surprised.

These were not tumors the way we normally think of them—a mass, a lump. Tumors can be removed; they have edges. These were “flare areas”, areas where the cancer cells were more concentrated but really the cancer cells were diffuse throughout the brain. One doctor explained helpfully “It’s like if you threw a handful of sand into water.”

In the early weeks we were rushing to find some sort of treatment, hoping Dad could hold onto some bit of his quickly disappearing vision. If we could stop the growth and progression of the tumors, maybe we could stop the blindness creeping in. The first medical team we worked with did not offer much treatment, as Glioblastoma is inoperable and incurable. But we wanted to do SOMETHING. We moved on to a medical team at the University of Washington that recommended a course of whole brain radiation followed by chemo, after which we would wait and watch. They told us that untreated Dad might live four to eight months, with treatment they hope to double that.

Looking back I sometimes wonder why we went ahead with whole brain radiation. My husband’s aunt, who had been an oncology nurse, warned me early on that radiation changes people. But at the time, of course, we didn’t know what would happen. We wanted to keep Dad from going blind. We wanted to keep him strong and mobile and himself. You just don’t have all the information when you’re making any of these decisions. You have to choose a course and go forward. You keep on choosing as you go, and sometimes you decide to stop choosing. All the way, it is your choice as a patient and a family. The choice is alarmingly and terrifyingly yours.

Reinventing the wheel

It is so hard to navigate the world of medicine. Everyone is different, every doctor is different, every cancer is different. One of the hardest things to accept is that the doctors don’t know exactly what’s going to happen either, or how long it will take.

Our friend Ken, who is a doctor, gave us some very good advice early on about questions to ask at our meetings with doctors:

1. What are we hoping for?

2. What are the goals of care?

Adding on to this, the most important things we figured out, based on good advice and trial and error, were:

1. Keep a notebook of doctor visits. Date everything, tape in business cards, write down who said what, write down phone numbers and what each person in the office does—as near as you can figure it.

2. Take notes at every visit because you will forget the main points or even the jist and walk out in a fog.

3. Actually, have a friend or family member come along to important doctor appointments because when big news and important information is being delivered you often go blank or cry or get angry and then can’t remember anything later. I was able to do this for my Mom whenever I was in town but my parents’ dear friend Ellen stepped in whenever needed. When I was able to attend, my Uncle Tom and Aunt Nancy or our friend Kelly came along to wrangle my son so I could be in the room.

4. Rides are a really big area where people can help. If friends are asking what they can do during the treatment phase, ask for rides.

Blind Guy drawing

In the first few months Dad still had some vision. He could feel his way from his chair in the living room through the kitchen to the bathroom and back. He could do exercises he devised himself in the backyard involving lifting and swinging a light metal-frame deck chair. He continued drawing his favorite subject, Blake Island, and things close at hand like his hand holding a coffee cup or pencil.

spilled coffee and mug, by Dave Leedy

He wanted to keep working on his novel and tried to dictate edits to my Mom. He talked on the phone with his friend John about a math problem they had been working on for several years involving ants—unless you are a mathematician, don’t ask. He kicked around a soccer ball with my brother Ben, really short distances.

He ran with me. I’d run just in front of him and call out to him “pot-hole coming on our right” “people up ahead, we are going to move out to the left around them” “uneven road here, Dad”. I made him a series of iron-on tshirts that said BLIND GUY, BLIND GUY RUNNING, BLIND GUY DRAWING. Partly this was genuinely to let people know he was blind. People jostled him and bumped into him shockingly, even once he got the white cane. I mean really, watch where you’re going folks.

But he quickly went blind and most of these activities dropped away. For a long time he would have visual fantasies or visions. The brain keeps firing visual imagery even when the eyes aren’t providing any information. He would see misty Japanese gardens from a Sumi painting one day, canyons opening below him the next. He often startled when you walked with him because he was seeingsome phantasmal object you were about to walk him right into. Why would you do that?!

The blindness was one of the scariest things to me. I can’t really think of anything scarier, except maybe endless pain. Which is actually a good thing about brain tumors. Weird thing about the brain, but the brain doesn’t feel pain. No nerve endings in the brain. And unlike many with brain tumors, Dad never really had headaches. He also sailed through radiation and chemo with only one episode of barfing and one small set of seizures. He was just kind of amazing through it all.

Dad’s response to the horror and unfairness of what was happening to him was to just let it all go. He handled it with utter grace and kindness. He was grateful for everything we did for him. He never grew irritable or angry or difficult. One of the nurses told us early on that radiation tends to make people more of what they are. So if someone was aggressive and angry, they might become more so. Dad became sweeter and sweeter.

Can you see anything from where you stand?

My Dad was amazing about the whole process, so open and generous with it. But he wasn’t really that interested in talking a whole lot about death or what was coming. He was pretty happy staying in the present moment and finding peace and pleasure everywhere he could. Sometimes I would press him about what he wanted, what he understood about his situation, what it felt like. As a poet and a pretty deep guy, we were hoping Dad would “write” or dictate something about his experience; we were hoping for deep thoughts about life and death from someone so close to the edge of existence.

But mostly the time slipped by in regular life chores and distractions. I spent most of the time I was there with Dad taking care of my son Hazard. I cleaned the house vigorously and cooked and helped Mom figure out the medical stuff. We had to make lists and schedules for medications, navigate appointments and treatment, handicap parking passes, bus schedules. All this became normal, unremarkable. I had moments of frustration when I felt like what I should be doing was sitting with Dad and holding his hand and reminiscing, or reading Patrick O’Brian’s Master & Commander books aloud to him. But when it worked best it was the small things like singing along to music in the car with him, making sure he could listen while I read bedtime books to Hazard, making him comfortable and refilling his coffee.

We didn’t have many of the searching talks I thought we might. Dad didn’t talk directly about his situation much and preferred to be out of the room when we had the hard talks with the doctors where things came down to numbers, months. But Mom did get this dictation out of him after a day picking out a Christmas tree with our friend Kelly; so very, very Dad.

As told to Mom by Dad and put into this sort of poem format by me:

So when people ask, “how are you”, you could just hand them the lab report

or say, Well I have cancer! But if you don’t want to come at people that way,

You could say, I have cancer, but I think I would never have had this day

the way it was without it and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

I wouldn’t mind the cancer going away, but if it’s not and it’s not likely to,

Let’s have some more days like this.

Cancer picks you up by the back of your shirt and says,

No, it can’t go on this way forever and you know that, don’t you.

Everything is a gift. This here cancer thing, I can’t call it a gift.

But this day, that was a gift. That was good. Following you all around,

Hearing everything I heard while we picked the tree.

Life in the slow lane

As the months went by the cancer was held at bay. The treatments were working! But Dad continued to deteriorate physically and mentally. We learned that the radiation treatment, which had stopped the growth of the tumors, was continuing to do damage to Dad’s brain. Many people who receive full-brain radiation for brain tumors don’t live long enough to discover this downside. Lucky Dad.

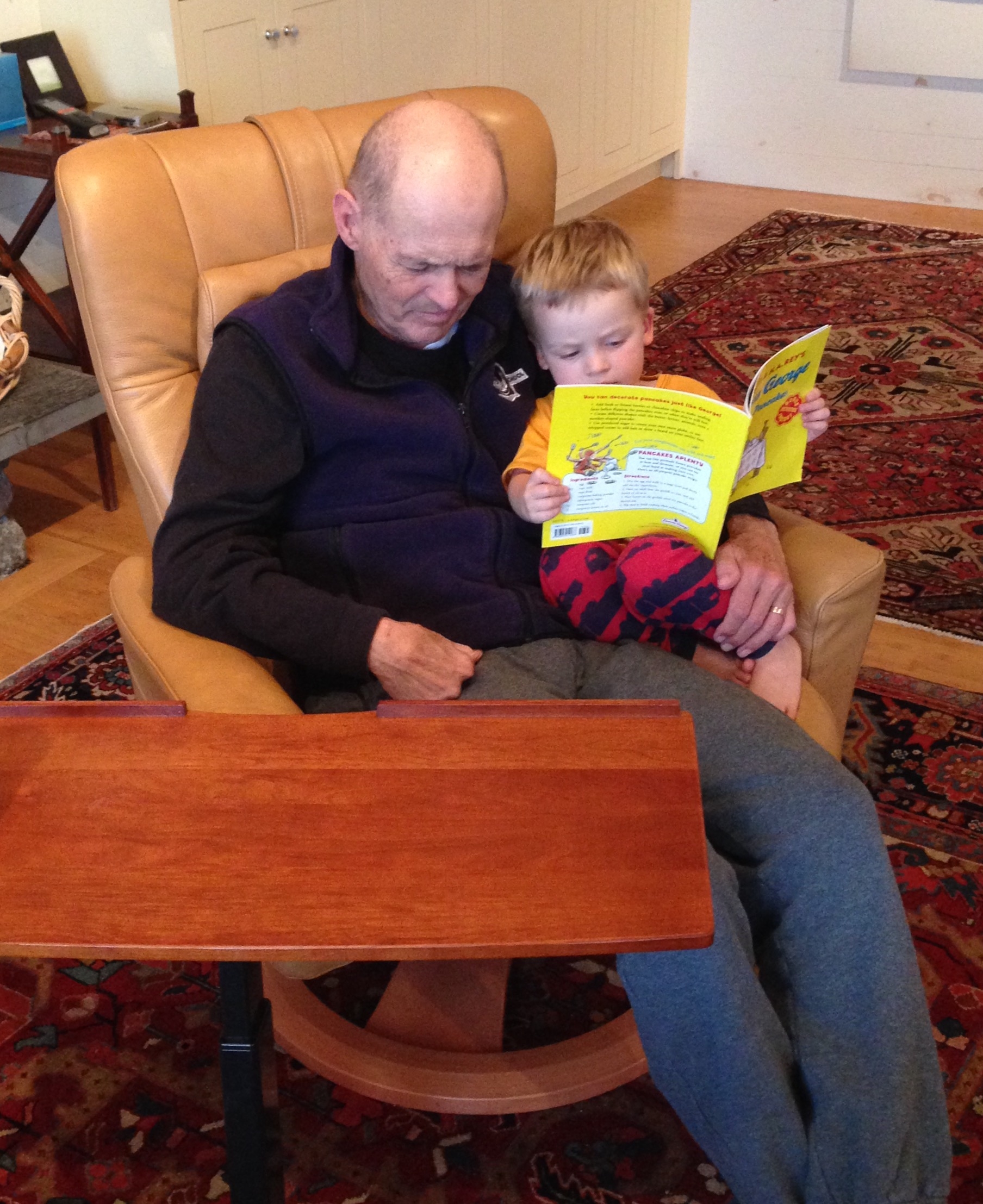

I visited in February during this phase and I saw what Mom was dealing with. The change in Dad and what her day-to-day life had become shocked me. This phase was so hard on Mom, but I genuinely think my Dad was happy. He had told Mom a few weeks before, “You know, a king could not be happier than I am right now. I’ve got you, I’ve got the kids, and I’ve got just the right number of grandchildren. The kids found great partners and they’re doing such a wonderful job bringing those kids up.” He was at peace, enjoying talks with friends, his family and “the baby symphony” as he called kid chaos.

Being a caregiver to a dying person is a bit like having a newborn—very difficult but doesn’t last forever. There was extreme sleep deprivation, physical tolls on Mom’s body, mental fatigue and boredom; the suspended sense of being out of control of your life. Throughout the two years of Dad’s illness and death, I was so impressed by my Mom’s pluck, stamina, good cheer and strength. She would’ve made a great nurse in either of the World Wars (favorite reading subjects of hers). She is not a complainer, not an agonizer. She always told me how her own Waspy mother raised her not to think she was so special or unique, but to be a good hard-working person. This humility and sensibility stood her well when coping with cancer.

The other thing that happens in the long haul of cancer is compassion fatigue in your friends. People really rally at the beginning and at the end; when someone is diagnosed and at death—bringing meals, offering help, stopping by. But cancer can go on and on. You are mostly on your own, possibly for months or years. Many friends stayed with us the whole way through. Some people didn’t visit because they didn’t want to intrude or be a bother or because they just didn’t know what to say; some couldn’t visit, it was just too painful. But Dad loved the visits. Every dying person is unique and there is truly no roadmap, so, if you’re wondering how to handle it, the best bet is to just ask. Ask if visits are wanted or if you can stop by with a meal. You really don’t have to say anything about the whole damned cancer deal, just show up and hang out. Tell stories about what’s going on in your life, a movie you’ve seen, an art show. Since Dad was blind, friends would come and read to him. Our friend Ken would read to him from the Economist and then they’d talk politics and rant, same as always. My brother Ben’s good friend from childhood Ben Campbell would come over and watch soccer games and provide the play-by-play description so Dad could follow along. This was also super helpful to Mom, who could then take a shower or a nap or a walk.

This was the hardest phase for me, aside from the initial diagnosis. I found myself getting mad at my Dad. It was a terrible feeling. There was a point where I felt that this was not really my Dad anymore, but a vampire who had taken over my Dad’s body and was feeding on him and holding us all hostage. Like a benevolent shell of him, with the same voice and way of talking but increasingly just a shadow of his wit and intellect and poetry. And suddenly after a full, rich life of being a regular (if unique and eccentric) person, here was my Dad…The Saint! It wasn’t right, it was too simplistic for the complex, flawed and wonderful human he was. I was mad about what my Mom was going through, about how hard things were for her. I was mad that everything felt on hold, that it was so hard to plan for the future with this huge unknown hanging over us. Mostly I was mad that I was losing my Dad bit by bit. And I felt worse for even thinking these things!

And no one knew how long this phase would last. A few days after Hazard and I had gone back home Mom wrote to Dr. Lynne Taylor, an excellent palliative care specialist we’d recently seen at Virginia Mason in Seattle, asking gingerly what she could expect in the next few months and whether Hospice was a good idea.

Dr. Taylor wrote back kindly and immediately. She couldn’t really tell us much except that Hospice was a good option. She wrote, “All it takes is the possibility that he might die within the next 6 months if the disease takes a typical course, but it is not obligated and I have had patients enjoy the benefits of hospice for up to two years.”

We liked that idea of “enjoying the benefits of Hospice”. Hospice is such a fantastic idea and resource. I wish more people could think of it not as the death knell and more as a way of easing the transition from life to death. But you do have to forego treatment. You have to leave treatment behind, and the idea that you might recover and live. For many this is a step that comes only in the weeks or days before death.

Looking back, the crazy thing is that Mom wrote this email after having been told by the doctors at the UW that Dad could possibly live for months or maybe years. This was daunting, given his decline and his total dependence. It turned out to be much quicker, in only three months he was gone. That is the thing with cancer; no one really knows how it will go or what that will look like. Every cancer patient and his family are reinventing the wheel.

one of Dad’s many Blake Island drawings from the year or so before he went blind.

Counting in days

On May 9, 2015 I got a call from my Mom telling me that Dad had taken a turn for the worse. He’d gotten suddenly sick. At first she and Karen, their amazing caregiver, thought it was the flu. But he had such a high fever and was so weak that they quickly called Hospice. The Hospice nurse told Mom he had three to ten days to live; she was right, he lived nine more days. Dad always was on the far end of the curve. The Hospice nurse told my Mom it was time to rally her troops. Mom called my brother Ben and me, and Ben started driving up from Portland right away. I was on a flight the next day and got there by the evening. When I arrived it was Hazard’s bedtime and Dad was in a hospital bed in Mom and Dad’s room, next to their bed. I sat right down and started singing all the songs I sing to Hazard at bedtime. Go To Sleep Little Baby, Me And Bobby Magee, The Universe Song from Monty Python’s Life of Brian, Unknown Legend, Sweet Baby James, Swing Low Sweet Chariot, Amazing Grace.

The first few days I was there Dad could talk and knew who everyone was. My husband Peter and Hazard flew in. It was great to have Peter there with his EMT knowledge and his level head. It was hard to have Hazard there. He wanted me to be his Mommy and I only wanted to be my Dad’s daughter.

My Aunt Jennifer arrived. Her husband, my Uncle Jake and my Dad’s younger brother, had died from colon cancer the year before. She had been through all this so recently, but in a hospital instead of at home. She stepped in and helped with everything.

My Uncle Tom, my Mom’s brother, and Aunt Nancy drove all the way from Western New York and arrived a couple days later. They came every day and stayed. My parents’ dear friends Debby and Mary came for what was supposed to be a weekend, drove home to Portland and then decided they had to come back. They came and stayed too. We all hung out in the room with Dad, talking and laughing and singing and crying. There were visits from Hospice nurses and from friends and dog friends. At one Hospice visit my Mom asked about getting Dad up safely to go to the bathroom. The nurse said he wouldn’t be getting up anymore. We switched to adult diapers. After that our routine included changing his “astronaut pants” as Mom called them to make it more acceptable. Seeing my Dad’s naked body, cleaning and wiping and diapering him as I had so recently done with my son, very quickly was not weird. My brother did the lifting while Mom, Aunt Jennifer and I did the cleaning and changing. We had to turn Dad side to side and prop him with pillows to prevent bedsores. Caring for him in this way had a ritualistic feel. It may not have really required all four of us, but it was comforting to share the task.

Hospice provided a box of drugs for pain relief at the end of life—mostly morphine. They also told us to put the Do Not Resuscitate form on the refrigerator. Most people have the goal of dying at home, surrounded by loved ones and expressly do not want to die in a hospital. But you have to work hard not to. If you want to die at home, the goal is to not call 911 or go to the hospital if something changes or happens but often people freak out; So you want to have those forms visible for EMTs who might show up in an ambulance. There is a great article called Death Is Not An Emergency by Robert Chodo Campbell, a Buddhist chaplain who works in hospice. This is so true! Death is not an emergency, It is such a normal thing, but it’s a heightened moment and one that is hard to think calmly in. Hospice prepared us for what the end would be like but you still just can’t imagine.

On the first day I was there I was telling Dad how I remembered being a little kid and trying to get his attention while he was watching a football game. “Dad, Dad, Dad, DAD, DAD!” He had an amazing power to tune me out and it used to drive me crazy. But now, I told him, as the mom of a kid who never stops talking, I totally get it! I told it as a funny story and was laughing at the memory. “Lorn,” Dad said with heartfelt earnestness, “I should never have ignored you.” I think about this moment so often, how important throwaway moments are; each one ripe with life.

Dad sort of plateaued for a few days. We took turns getting out. I would run or go for walks with Hazard and Peter. Jennifer cooked. We had amazing family meals every night including anyone who had stopped by to visit. We all drank a fair amount. It felt strange to be out in the dining room talking, eating and laughing while Dad was alone in the bedroom. But he mostly slept or was not very conscious. We kept talking to him until the end. I told him everything I wanted to tell him, thanked him for everything he’d given me, told him it was okay to go and that I’d be okay. Friends came and did the same. Friends also came and sang and played music for him. In the beginning he would sing along, later he would almost smile and squeeze a hand. He didn’t open his eyes much.

Every day I would wake up with the thought “is he still alive?” followed by “will today be the day?” One morning Mom was sitting on the hospital bed with him, holding his hand and he said “the more contact the better.” On the last day we knew things had changed. In the early morning Dad talked to Mom a little, said “it’s another day” and smiled and seemed at peace. But then soon after his breathing changed. “Is this the death rattle?” We asked each other in whispers. He seemed very far away. He winced when we moved him. His fever spiked. We gave more and more morphine.

That night Peter and my brother and Mary and I were sitting with Dad. In my memory, Ben and I were sitting on either side of his head while Peter and Mary were sitting at his feet. We felt like this was the end but you never quite know. My Uncle Tom came in, stricken and weeping, and said “I don’t know how to do this, this is all wrong.” I reassured him that no, this was okay, we were doing it right. He sobbed and then put both his hands on my Dad’s head. That’s when Dad took his last breath, at 9:20pm. When Peter took Dad’s pulse and said “he’s gone” I burst out crying and kind of laughing and yelled “you did it!” I felt so proud and so relieved that he’d made it; he’d crossed over. I think my brother and Peter and Mary and I all put our hands on him. Tom was stunned and went to tell my Mom. My Mom and Nancy and Tom and Jennifer and Debby and our friend Ben Campbell all came in. My Mom sobbed and sort of flung herself on Dad. We all talked at once. Peter went to call Hospice and the Funeral Home. We all left the room except Mom, who spent some minutes alone with Dad.

Later we drifted back and some of us sat around the bed. My Mom and Jennifer and others sat in the living room telling stories, laughing, drinking wine and starting to plan the next steps. We’d all started talking about these plans, so some of it was already outlined. We had to call people, tell the family and close friends. There was so much to do.

The funny thing is that in writing this I feel like I have such clear memories of certain parts and such a blur for others. Over a year later I checked my memory with the others in the room—Peter, Ben, Mary and Uncle Tom—and we all remember things slightly differently. Maybe we all held onto different bits, maybe we saw what we needed, maybe memory is a slippery sea creature.

We learned later that in Buddhist belief, holding a dying person’s head helps him on his way. Without knowing it or thinking he could, Uncle Tom did exactly the right thing.

The nurse/EMT sent by Hospice arrived to declare Dad dead and turned out to be the father of an old soccer teammate of my brother’s. He’d stood on many soccer sidelines with my parents over the years. In the midst of it all, we laughed with wonder and Mom and Ben managed to say specific and kind things about what an artful player his son was, what quick feet he had. The Hospice nurse got rid of all the leftover drugs, mixing them with ground coffee and water in a Ziploc bag and putting them in the trash. When he was done checking Dad’s body and filling out papers Peter organized us to move the furniture so the funeral home people would be able to roll Dad out. The guys from the Funeral Home arrived around midnight, I think there were three of them. The funeral director had on a shirt unbuttoned one button too far, revealing a lot of chest hair. Mom, Peter, Ben and I stood on the deck looking at Blake Island while they took Dad’s body away. Then Peter organized us again to break down the hospital bed and move it out to the carport, move the furniture back and make the room feel like Mom’s bedroom again. It was late when we finally went to bed. I took one of Dad’s anti-anxiety pills and slept.

Aspens, by Dave Leedy

Not resting in peace

When someone dies from cancer it is the culmination of a long period of weirdness, suspension and limbo. So many things have been uncertain and on hold. You get good at living day to day. “There are good days and bad days” becomes a go-to response when people ask how things are going. Even in the last days, the last hours, you don’t know how long you have or what will happen next. Then when death actually and decisively happens this all changes instantly and it is incredibly shocking. You know it’s going to happen for so long and feel ready but when it does happen you are not ready at ALL for what comes next.

Dad had a great death. It was really amazing, everything you’d wish for: at home, family and friends gathered, very little pain and suffering, surrounded by music and singing. It was a homerun of a death and we all felt pretty great about it, like we really nailed the death. The week after, leading up to the Memorial, was hell. You need a Death Planner even more than you need a Wedding Planner. Your brain is just not working and the simplest things feel so impossible and incomprehensible.

Suddenly you have to notify all the family and friends, deal with arriving relatives and friends (who are often surprisingly helpless and want YOU to tell them what they should do and help them plan their trip), work with the funeral home, write an obituary, choose the clothes that your Dad will be burned in, and plan a memorial with everything that entails—date, location, parking, music, program, slideshow, speakers, remarks, food and drinks. It is terrible and it all happens in a very short time. My Dad died on a Saturday night and the memorial was the next Friday. It was like planning a wedding in a week when you’ve just had a lobotomy.

There was one day in the midst of the hell week of planning when I was struggling to get the program for the memorial laid out. My Mom didn’t have Photoshop. I was calling around, trying to find someone who had it and finally drove to a local print shop to use Photoshop on their computer. But my document was in Pages, because that’s what was on my Mom’s computer, and they didn’t have Pages. They could not possibly think of any way to help me or do anything remotely useful, like step in and put an arm around me and say “Oh sweetie, this must be so hard for you.” Followed by, “Let me just take care of this for you real quick. Have someone pick them up tomorrow at 3pm.” Finally I burst into tears and may have yelled at the hapless clerk before storming out. In my car I sat blankly sobbing until it occurred to me to just ask a friend. I called my friend Gina and asked her to take care of it and she took care of it. She laid out the program and got it to a different print shop and also picked them up. But it took me about two days of suffering to figure this out. When you’re going through the aftermath of death, you don’t even know what you need. You don’t know what help is needed or how to ask for it.

Getting it wrong, getting it right

When big stuff like death or illness comes up I’ve found that a lot of people dither; even people who are ordinarily very clear-headed and decisive. This may be you or it may be the people around you, or all of you. People suddenly lose their way and don’t know what to say or do. Don’t be surprised by this and don’t be too hard on your people. Some people are really good in crisis. They shine, they anticipate, they support. These may not even be your closest friends. Your closest friends may stay away out of fear or shame or denial or grief. There are people who love to visit sick people and people who can’t stand it.

When someone dies who is close to you, or close to someone you love, knowing what to do is so complicated. We do our best. We don’t always get it right. Sometimes you have regrets. What I would urge is just try to get it right next time. People keep on dying, you will have more opportunities to get it right!

When Dad was diagnosed my husband Peter and I quickly decided to just go and be there as much as possible. This was partly because we’d faced this situation before and had not been there enough. My mother-in-law Honey died in 2007 from Inflammatory Breast Cancer, a virulent version of breast cancer. She had refused nearly all treatment and fought hard to the end, insisting she was not going to die, that Jesus had promised her. While she was sick Peter was offered his first permanent job with the National Park Service, the first step in a lifetime career. The big drawback was that it was on Isle Royale, probably the most remote National Park in the lower forty-eight states. Isle Royale is an island in Lake Superior, a five-hour ferry ride from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. We would live on Amygdaloid Island, a tiny island off the remote west side of Isle Royale and an additional one hour boat ride from Headquarters and the ferry dock. We debated over whether to take the job, whether to go back to Peter’s seasonal job at Mt. Rainier, whether to go be with Honey and Karl (Peter’s stepdad). We took the job, with Honey’s support. She was always an iron-willed advocate for her boys and wanted more than anything for them to succeed and find their paths in life. We visited as her health deteriorated but it wasn’t really enough; the bulk of the responsibility and care was left to Karl and Peter’s brother Tim. We were there a few weeks before she died but then we had to go back. When she died we got a call on the radio from Park Dispatch and had to climb a ladder on the side of the water tower to make the satellite phone call to hear from Karl that Honey had just died. We left as soon as we could get on a ferry, which didn’t run every day, took the five-hour ride to the U.P., spent the night, then had an hour flight on a small plane followed by another flight. We were there for the Memorial Service and the aftermath but we weren’t there for the real end.

In the few days we were there before the Memorial Service, friends called and offered condolences and offered to fly out and help. “No, no,” we said, “it’s okay, we’re doing okay” not wanting to put anyone out or for them to spend their scant funds on last minute plane tickets. We were doing okay. But then Peter’s friend Moonglow called and said he had a ticket, would be arriving the next night and could someone pick him up? It was just such a relief and such a great feeling. It was so good to have him there, so helpful and so easy. Maybe the best part was that he didn’t ask if we needed him or if he could help; he didn’t really ask anything of us. He just showed up and helped out where he saw the need. He made us laugh, drove the car, picked up food, talked to relatives. He was there. Just being there can be huge. For me, this was a lesson.

I have always regretted not being there for more of Honey’s last days. I wish we’d been with her at the end. We did what seemed to make sense at the time, but it didn’t end up feeling good, or right. When my Dad got diagnosed, Peter and I both agreed we were going to do things differently; we were just going to be there.

We get so stuck on plans. You have something planned and it’s on the calendar and then something crazy comes up like the imminent death of a family member or dear friend and you just can’t figure how to square these things. So many of us have difficulty acting decisively in a moment of change and uncertainty. It is so hard to change the plan, toss it out the window and make a new plan. But I would urge you in your own life to look for those moments when something big and unexpected is happening and rise to the occasion. Change your plan and be there.

I did this Imaginary Funeral for my Dad not too long after he was diagnosed. He could still see enough to write the list, though the lines veered off and wobbled like a blind contour drawing

So what can I do?

So you may ask yourself, how can I be helpful to my friend who has just been through a death?

What should I say or not say?

Not helpful:

1. Can I do anything to help?

2. What can I do to help?

3. Will you let me know if I can….you get the picture

4. Just tell me what you need

5. Can I pick anything up for you?

These are not helpful because they are not specific. Immediately after a death you really can’t think. You can’t do much besides stare and maybe cry or laugh. A lot of staring out windows or into space goes on. It is so hard to make decisions or plans, and everyone needs you to. The best thing you can do for someone who has just been through a death is make specific offers. Don’t ask them for anything, including information, guidance or their wishes. Assume they don’t know.

Helpful:

1. Can I come over and clean your house?

2. Can I take your child to the park for two hours at 11am tomorrow?

3. Can I come over and play with your child while you go for a run/take a nap/cry/have sex/write an obituary/take a shower/put your Dad’s clothes in bags for Goodwill?

4. Can I bring you dinner tomorrow night? Or on Tuesday?

5. Your out of town relatives can stay at my house and drive my car.

6. I’ve arranged the catering and the location for the Memorial

7. I’m bringing wine and chocolate. Would it be okay to stop by at 5ish?

When someone dies, lots of people write letters and notes of condolence. My grandmother called these “grief notes”. They can be sweet and beautiful and wonderful. They can also be painful and a burden. I could not bring myself to read a single note. My Mom read every one. Even when she laid out the nice ones she thought I should read, I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Mom appreciated all the stories and thoughts, I felt weighed down by them. A practical tip is this: if you write a grief note and the bereaved person writes a thank you note, do NOT write back to the thank you note. Then they will just feel guilty and like they need to write you again. Just writing thank you notes for condolences is a tremendous effort (which I personally think shouldn’t be necessary, but according to my mother this depends on how you were brought up).

As far as what to say, which we all wonder about and feel awkward about, you do want to say something; an acknowledgement is good, just keep it brief. To me it’s weird if people don’t mention the death or say anything about it because it’s this huge thing you’re carrying. A good thing to say is “I’m so sorry” and then move right on. Or you could say, “I lost my Mom/Dad/husband/grandmother last year. So hard,” and that’s enough, really not much more.

Don’t start telling your story. This is really tempting because you want to relate, commiserate, empathize. You also probably really want to tell your story because it sucks to lose someone and when it happens to someone else, it brings it all up again for you. But DON’T DO IT. This is not your time; maybe later, after a few drinks. Going through cancer-illness-death you do a lot of listening to other people’s stories. Everyone has one; some are helpful, most are not. And keep in mind the sheer number of people the bereaved person is dealing with. Quick acknowledgement, then move on. If they want to talk about it, believe me they will.

While I wanted some sort of acknowledgement, my Mom really appreciated the reaction of most people in North Park, CO where we have a cabin. There was a big meeting my Mom attended later in the summer and everyone knew Dad had died. Only one person said anything to her about it. She liked it. Mom had dinner with one local friend and her friend just said, “It happens.” It DOES! That’s the crazy thing; it just happens and happens.

So there you go, everyone’s different; just do your best.

I call this drawing of Dad’s Exploding Garden. I don’t really know what it is, I found it after Dad was already blind and couldn’t really answer this sort of question.

The problem is the problem

Right after Dad died Hospice of Kitsap County dropped off a pamphlet called “Uncomplicated Grief Symptoms”. It’s like What To Expect When You’re Expecting except more What To Expect When You’re Grieving. It boiled down to this: symptoms of grieving may be everything and its opposite.

I had many of the symptoms on that Hospice list—feelings of numbness, anger, irritability, sadness, anxiety, relief and mood swings. I had sleep disturbances, dreams of the deceased, restlessness, over-activeness, crying. I had confusion, lack of ability to concentrate, problems with decision making, increased sensitivity to positive and negative attention, role changes, need for rituals.

In the week after Dad died I would lie in bed before falling asleep and memories and thoughts of him would come to me. It was nice, mostly good memories from before he was diagnosed, little gifts of visions.

After the Memorial people started going home. First our California family left, then my brother and his family, then Aunt Jendo, then Peter. Hazard and I stayed with Mom. We celebrated Hazard’s third birthday with a party my considerate and close-listening friends Norma, Angie & Gina offered to throw and handled completely with only the most minimal check-ins and effort from me. At the end of June Mom and Hazard and I drove to our cabin in Colorado; for all of us, one of our favorite places in the world. We stayed at the Ranch with Mom for a week and then flew home to Texas.

In the weeks on the Island with Mom before I went back home I threw myself into mundane organizational tasks (not that this is so out of the ordinary for me). I cleared out and reorganized all the closets in the house, threw away old toiletries, refolded all linens and reorganized my Mom’s drawers. I plotted against the utility room and the boxes of CDs gathering dust. The shoeboxes and folders of old pictures and letters gave me physical discomfort, like an itch. But the purging and sorting didn’t satisfy. I kept feeling disorganized and out of sorts. It hit me one day in the shower that the problem was that that Dad was DEAD. That outrageous problem was unsolvable. No amount of organizing would untangle it and no strategy could dodge around the grief in it. This made me feel a little better, or a bit less crazy. I came up with the following points and repeated them to myself:

1. You can’t skip this grief thing

2. No one is exempt

3. You will do it sooner or later

Once I got home and for those first months I cried a lot and I was angry a lot. I had an incredibly short fuse and little things would send me into rages. I was very hard on Peter and not the best most patient mother. When I was grieving and angry and kind of a wreck Peter was the closest person at hand to take it out on, and really the only person given that we lived in isolation in a remote National Park. He was also the safest person to it take out on; I knew he forgave me, loved me and had great powers for letting things roll off. I was mad at him a lot. It was totally unfair and felt terrible for both of us and he handled it with amazing grace and forbearance. He kind of just let me go until I ran out of steam, or the tears to fuel it.

For a while I cried every day, often while driving and always while listening to music. Little things would remind me of Dad and I’d be caught all over again by the sorrow and pain. I’d hear a song on the radio and think, “Oh, I’ve got to tell Dad about this singer, he’d love this!” and then remember that he’s gone. It was just endlessly surprising and sad.

Just the other night I walked into the bathroom and caught my reflection in the mirror and it was just my Dad looking at me—the one eyebrow a little lower than the other, the serious expression and the set of the mouth. Even now, years since he died, this undoes me.

Things That Make Me Think of Dad:

1. Sweeping the driveway

2. Worcestershire sauce

3. Pretty much all singer-songwriter music

4. Mopping the kitchen

5. Any kind of plumbing issue

6. Cooking a stew or soup that involves beans, canned tomatoes, various vegies and cilantro

7. Swishing water in my mouth post-toothbrushing and spitting. Also the word “ablutions”

8. Hazard raising one eyebrow

9. Bach cello concertos played by Yo-Yo Ma

10. Leaning over and sucking spilled wine directly off the counter

Finding what’s missing

It’s been over three years since Dad died. The one-year anniversary was really tough. The whole month of May was tough really, which is unfortunate as Hazard’s birthday is at the end of May. I had a whole resurgence of anger and impatience.

My Dad was such a sweet and gentle person. I always felt loved and supported and approved of by him. Now, this source of unconditional love is just….GONE from the world, irreplaceable. A few months after he died I was overwhelmed by the feeling that all the sweetness had gone from my life. I got mad at Peter for not being that source of sweetness. Peter is a joker, a trixter, a supportive and creative partner and a great listener and communicator. But he’s very different from my Dad. While this is probably one of the reasons I chose him, in the throes of grief this technicality did not protect him. Peter listened to all this and agreed with most of it but suggested that there was someone left who had these qualities—my brother.

One really good thing to come out of Dad’s death and the hard year after has been texting with my brother. My brother and I text each other whenever we have one of those Dad moments, a reminder or a wave that just hits us out of the blue. This, and his presence in the world, is immensely comforting to me.

It also occurs to me that some of my Dad is in me. I hope some of his sweetness made it in and that I can nurture it and learn to give it to the world the way Dad did. It’s a thought that gives me something to focus on. I thought about him this morning as I swept the driveway. What a pointless and Sisyphian zen task, sweeping the driveway on a windy day. But I get why he did it more and more and this makes me feel close to him.

For me, sweeping the driveway is something I can be in charge of and find some satisfaction in. In my life as an Artist Mom living in an isolated part of a remote National Park, I don’t get to set my own agenda all that much; I’m keeping a very active little kid busy and engaged and taking care of all the minutiae of life while trying to keep thinking thoughts I can make into objects and images.

When I was a kid my Dad was a poet and artist and philosopher squeezed into a normal and rich life of kids, teaching, dogs, marriage—football on TV while folding the laundry. I think about him sitting at his table staring out the window, writing or thinking. I think about him sweeping the front walk of pine needles or mopping the kitchen floor, tasks he performed nearly daily. Now I think he was doing more than just sweeping and mopping. He was giving attention and meaning to the small pieces of his life. At least, that’s what I think. I will be thinking about him, sweeping with him and finding other ways to keep him with me for the rest of my life.

Here’s a poem I wrote for Dad

The Economy

I think of Dad most while cleaning.

I remember him via vacuum and broom.

How many Lego pieces have I vacuumed up over the years?

How many paperclips? Pennies?

I think this is how the Economy works,

All these small losses of nickels down flood drains,

piggy banks buried, money under mattresses,

coin jars by the bed.

And the big one—presence turned to memory.

No forward motion, no new images from that day forward.

Just Dad sweeping the front walk with total focus

And that great side to side to side dancing rhythm

Sk-sk-sk-sk

Dad and Nikka running on Moonlight Beach in Encinitas, CA, his hometown

post script 10/17/18

Last week I got an email out of the blue from a friend of Dad’s, Colleen Mariotti, saying that she’d just found some drawings Dad did while he was going blind. Dad taught Colleen’s kids and was crazy about them. The family visited while he was sick before they departed on a multi-year world traveling adventure. Dad gave the kids some of his recent drawings. I hadn’t had a chance to take pictures of them and one of them was a real favorite. I later asked Colleen if she could send me a copy but they were in storage while the family traveled, then the storage unit was broken into and ransacked and we thought that was it for the drawings. Amazingly, the drawings just turned up in a box of special things stored with grandma and Colleen just sent them to me. Getting to see this one again is a real gift. Thank you Colleen!

Dad’s notebook and sunglasses